The Monument: A Hidden Gem in plain sight

by Sarah Brierley

Sited at the northern end of London Bridge is a “really tall stone stick with a gold thing on top”. Well, that is how one child on a school trip described it, at least. The child in question was of course referring to the Monument to the Great Fire of London. It is indeed situated at the northern end of London Bridge, but its once prominent site is now rather obscured. Meaning that it really is a gem hiding in plain sight.

So, what is it? Who designed it? Why is it there?

What is it?

A good question, and one that can be answered in many ways depending on who is asking. First and foremost, it is a monument built to create a permanent reminder of the Great Fire of London in 1666. Fires were incredibly common in medieval London, and to a lesser degree, still common in the 1600s. However, they were usually dealt with very quickly, limiting damage to a small area. The Great Fire of London is classed as one of the most significant events in London’s history because of the immense destruction it caused.

The summer of 1666 was incredibly hot and dry. This led to the wooden houses drying out, effectively making them perfect kindling for a fire. The time at which the fire started was also a factor. It ignited in the early hours of the morning when most Londoners were asleep. This contributed to the initially slow response. And then there was the wind direction. The wind in London normally blows from West to East, which would have blown the fire away from the centre of the city. In September 1666, the wind blew the fire right into the heart of the City. It is estimated that nearly 80% of the City of London was destroyed. This included 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches and nearly all the civic buildings.

The destruction was on an unprecedented scale. Therefore, it was seen as a positive step, that following the rebuilding of London, a monument would celebrate the City that rose from the ashes.

The question can also be answered from an architectural standpoint, in which case, the Monument is a Doric column built of Portland stone topped with a gilded urn of fire. It comprises of a base, the column with an internal spiral staircase culminating at a viewing platform and the decorative urn.

However, as well as its commemorative purpose, it also had a part-time job as a scientific instrument: a giant zenith telescope designed to observe the stars and celestial objects directly overhead. To enable this, a hinged lid in the urn (the “gold thing on top”) opened to the sky. It was also intended to be used for gravity and pendulum experiments. Hidden underneath the floor of the modern-day ticket office, a trap door leads to the underground laboratory. However, the surrounding traffic (yes even in 1666, those pesky horses and carts) caused too many vibrations, rendering the laboratory all but useless.

Who designed it?

Again, another intriguing question that is open to debate to this day. For the answer we need first to look back to what happened after the Great Fire. We have touched on the destruction it wreaked on London. Essentially London needed to be totally rebuilt. Step in Sir Christopher Wren, a man who needs little introduction. He is most well known as the architect of St Paul’s Cathedral. What people are sometimes not aware of is that he was also an astronomer, a mathematician and a physicist.

In the months preceding the Great Fire, Wren had been awarded the contract to repair St Paul’s Cathedral by King Charles II. The repair also included a redesign and the addition of a high dome. But work hadn’t even started before the Great Fire struck. So, as Wren already had the King’s confidence, he was then tasked with helping to rebuild the City of London, including St Paul’s Cathedral, many churches and the Monument. But it was impossible for one man to design so many buildings at the speed needed to rebuild London. So, for some buildings and churches, Wren signed off the final designs rather than design them from scratch. This applies to the Monument.

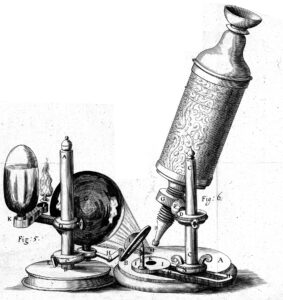

Wren had a scientific buddy called Robert Hooke. Hooke was an immensely talented man in many areas of science – as a physicist, astronomer, geologist, meteorologist and architect. He formulated the law of elasticity, contributed to the wave theory of light, and is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living things at microscopic scale, using a compound microscope that he designed; his book Micrographia revealed the structures of fleas, lice and other organisms.

There are existing plans for the Monument by Robert Hooke that show the plans for the structure we see today and they show Wren’s signature of approval. And this leaves us now with the last question….

Why is it there?

This is perhaps the easiest question to answer. The position of the Monument is very specific and apt. It stands at the junction of Monument Street and Fish Street Hill. It was built on the site of a church called St Margaret, and this was the first church to be destroyed by the Great Fire.

Now for the specifics, the Monument is exactly 202 feet (61 metres) tall, and exactly 202 feet to the west of the spot where the Great Fire started on Pudding Lane. No one can say it wasn’t given a lot of thought. However, things are very different for the Monument in 2025. When it was built it was incredibly prominent; it could be seen easily from afar. Modern life has now encroached on it, and subsequently it is effectively hidden in plain sight. Tall buildings surround it like a protective ring. As you walk across London Bridge from the south, just after exiting the bridge, if you glance to the right, it appears, soaring to the sky. Even on a grey day the glint from the urn (some say orb) is delightful.

So now you know more about this hidden gem, why not pay it a visit? Climb the 311 steps to the viewing platform, and you will be greeted with wonderful panoramic views of the City of London and the River Thames .  A small note of caution though – the climb isn’t for the faint-hearted. There is only one way up and one way down! There is no lift, but you get towalk on the very steps built in the 1600s. People are marvelously polite and make way for those ascending and descending or taking breathers. The stairs are relatively narrow but the wonderful staff at the ticket office always control the amount of people inside. The icing on the cake? As you leave, you’ll be presented with a charming certificate to reward the effort you made after the climb…oh and you also get great photos from the top – and a chance to see a pigeon’s eye view of London.

A small note of caution though – the climb isn’t for the faint-hearted. There is only one way up and one way down! There is no lift, but you get towalk on the very steps built in the 1600s. People are marvelously polite and make way for those ascending and descending or taking breathers. The stairs are relatively narrow but the wonderful staff at the ticket office always control the amount of people inside. The icing on the cake? As you leave, you’ll be presented with a charming certificate to reward the effort you made after the climb…oh and you also get great photos from the top – and a chance to see a pigeon’s eye view of London.