How should Britain tell the story of its slave owning past and how do you contextualise a slaver? That is the question the City of London Corporation faced following their decision in October 2021 to retain the statue of the slaver William Beckford in Great Hall. As well as the statue of Beckford, the City of London Corporation is also the custodian of a statue of John Cass, another slaver, whose name until recently had graced a charitable foundation, primary school and business school. Both statues are still on display, and as Guildhall Great Hall is again open to the public, we thought we would take a closer look at the statues and examine the City’s dilemma over what to do with its slaver statues.

The William Beckford Statue

William Beckford hailed from a family that made its fortune from sugar cane plantations in Jamaica and his father was so rich that he was known as Alderman Sugarcane. Like many slave owners, Beckford inherited an enslaved workforce when he inherited his father’s sugar cane plantations and eventually owned 13 sugar cane plantations and 3,000 enslaved people.

Beckford was a prominent businessman and member of society in his own right, was twice Lord Mayor of London and a noted defender of liberty and John Wilkes, a radical politician and journalist who often clashed with the establishment when seeking political reform. Beckford was also an absentee landlord, being based in England, and his treatment of enslaved people was brutal, killing 400 people following a slave rebellion on one of his plantations in 1760 and punishing the leader of the rebellion by burning him alive. Ironically, his records show that he owned two enslaved people named “Liberty” and “Wilkes”.

So why is Beckford memorialised in Guildhall? In fact his statue was the first to be placed in Great Hall in 1772 and began a tradition of Great Hall being a repository of statues of the great and good – all of which unsurprisingly commemorate white men. Beckford’s statue is here as the City wanted to show their respect for a speech Beckford made when meeting King George III in 1770 in which he defended the liberties of the City and daringly admonished the king by alluding to the fact the king could be replaced. Beckford died from a chill soon after making this speech and no doubt sentimentality played a part in the City deciding to honour him.

The committee in charge of erecting the monument ran a competition to choose the design of the statue and specified that the text of the speech should appear on the statue and depict Beckford giving the speech. The design they chose was by the sculptor John Francis Moore, and his statue captures Beckford in full-flow when making this speech to the king – he is wearing his mayoral robes and his chain of office, and he is gesticulating to emphasis what he is saying. Either side are two female figures representing Commerce and the City of London, both in attitudes of despair, mourning his death.

However, a sketch of a possible alternative design for the statue shows Beckford again in mayoral robes with a figure of Britannia beside him, leaning into Beckford in a gesture of affection and gratitude, while Beckford stands on the back of a manacled black man. The design is staggeringly shocking – firstly because it is an unashamed acknowledgement of the source and exercise of Beckford’s power and riches, and secondly because it seems this image was considered appropriate for a memorial celebrating the defence of liberty. There can be little doubt that had this been the chosen design, the statue of Beckford would have been removed from Great Hall long ago.

The John Cass Statue

In addition to Beckford, the Guildhall has a statue of Sir John Cass, an MP and philanthropist, who was a key figure in the Royal African Company, which was the company set up by the Duke of York (later James II) and which had a monopoly on the slave trade in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The RAC transported over 150,000 enslaved people across the Atlantic into a life of misery.

His statue originally was on Aldgate High Street and was commissioned by The Portal Trust (previously the Sir John Cass Foundation) in 1751. Due to Cass’s extensive philanthropy, a primary school and business school also bore his name, both of which changed their names to The Aldgate School and Bayes Business School respectively as a result of the Black Lives Matter movement which called for the removal of public monuments honouring those involved with the slave trade.

The Decision to Retain and the Explain

The Black Lives Matter movement led to a spotlight being shone on these statues, particularly after the statue of Edward Colston, who had long been the subject of a campaign to remove him, was toppled and thrown into the Bristol Channel on 7 June 2020. This led other bodies to examine their own statues and the statue of Robert Milligan outside the Museum of London was quietly removed, with the intention that it will form part of the Museum’s London, Sugar & Slavery Gallery which explains London’s role in the slave trade.

The City of London Corporation embarked on a public consultation about its statues, initiated by the City’s Anti-Racism Taskforce, which found that of the 1580 respondents, 71% of respondents wanted the statues of William Beckford and John Cass retained, whereas 75% said the statues should be contextualised or removed. Initially in January 2021, following the recommendation of the City’s Anti-Racism Taskforce, the Corporation decided to remove the statues.

A Working Group was then set up to consider the future of the statues and a second consultation was held, which only consulted 467 City stakeholders (such as City employees and officials and Guildhall clients) and this resulted in 42% of respondents saying the statue should be retained and explained, and only 39% wanting the statue to be removed.

Following the Working Group’s report, the Common Council decided in October 2021 to keep the Beckford statue in Great Hall. Factors influencing this decision were the cost of removal (estimated to be £100,000) and that Great Hall is a listed building and consent would have been required.

The Common Council’s volte face also reflected the government’s view of what to do about contested statues and prior to this decision in September 2020, the then Culture Secretary, Oliver Dowden, had written to museums urging them to follow a policy of “retain and explain” with regard to contested statues saying: “History is ridden with moral complexity. Statues and other historical objects were created by generations with different perspectives and understandings of right and wrong. Some represent figures who have said or done things which we may find deeply offensive and would not defend today. But though we may now disagree with those who created them or who they represent, they play an important role in teaching us about our past, with all its faults. It is for this reason that the Government does not support the removal of statues or other similar objects.” At a subsequent meeting with museum leaders in February 2021, Dowden was reported as saying that he wanted to “defend our culture and history from the noisy minority of activists constantly trying to do Britain down”. This provoked concern amongst some members of the heritage sector and the Museums Association issued a statement saying they unreservedly support “work to decolonise museums and their collections and to broaden and deepen our understanding of the legacy of empire and slavery.”

Is a plaque enough to contextualise a slaver statue?

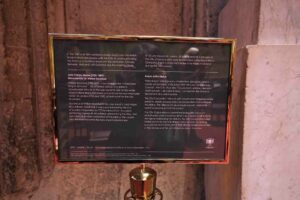

Guildhall is again open to the public, and you can view the Beckford statue in Great Hall and the John Cass statue in a corridor outside the hall, and both now have a small portable sign placed beside each statue. The plaque for Beckford acknowledges that he was a slaver, and both signs explain that 15 Lord Mayors, 25 Sheriffs and 38 Aldermen were shareholders in the Royal African Company, but neither explain the role of the RAC in the slave trade, even though the sign for John Cass mentions that he was a member. The signs further explain that the City Corporation will work with a youth and intergenerational panel to create a plaque for both Beckford and Cass that recontextualise and reinterpret the statues. I can only presume that these portable signs are therefore a temporary measure and the final plaques will have more information.

Is putting a plaque next to a statue enough ? The argument for contextualising statues and street names in situ is to ensure that difficult periods of history are not erased and forgotten. If we remove all the slaver statues, are we brushing this shameful period of history under the carpet and risk allowing the issue to slip from public consciousness? Britain is in the midst of a painful process of acknowledging its past, but leaving statues in place is not the only way to memorialise past wrongs or to explore difficult issues. Placing a statue in a museum can offer far greater scope for contextualisation and memorials, such as Stolperstein (German for stumbling block) which are brass plaques placed in the pavement where a person who was killed by the Nazis lived or worked, can be a much more effective way to remind people of a great wrong.

Lastly, what we should also consider is that most of the statues we have, and according to Dowden should retain, are of privileged, white men. Statues tell us who is worthy of honour and respect in our society and create a display of power we subconsciously consume. If we were to look at these statues we would conclude that power rests in the hands of white men and they are untouchable, regardless of how we now view them. That has certainly been true for most of history, but society is changing and so should the statues.

The views expressed in this blog are the author’s own.

Visit Guildhall by booking a guided tour or come on the Slavery and the City tour to learn more about the City’s connections to the slave trade.